|

July, 2005

Aug. 2005

Sept. 2005

Oct. 2005

Nov. 2005

Dec. 2005

Jan. 2006

Feb. 2006

Mar. 2006

Apr. 2006

May 2006

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

February 2009

March 2009

April 2009

May 2009

July 2009

August 2009

September 2009

November 2009

December 2009

January 2010

February 2010

March 2010

April 2010

May 2010

June 2010

July 2010

September 2010

October 2010

November 2010

December 2010

January 2011

February 2011

March 2011

April 2011

May 2011

June 2011

July 2011

September 2011

October 2011

December 2011

February 2012

April 2012

June 2012

July 2012

August 2012

October 2012

November 2012

February 2013

May 2013

July 2013

August 2013

October 2013

November 2013

April 2014

July 2014

October 2014

March 2015

May 2015

September 2015

October 2015

November 2015

August 2016

March 2017

January 2019

May 2019

August 2019

March 2020

April 2020

May 2020

July 2020

October 2020

January 2021

February 2021

August 2021

January 2022

February 2022

April 2022

June 2022

August 2022

September 2022

December 2022

February 2023

ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS NEWSLETTER

Gloria Mindock, Editor Issue No. 114 April, 2023

INDEX

Cervena Barva Press April Newsletter, 2023

Hi everyone!

The big news is that Cervena Barva Press is celebrating 18 years as of April 1st.

Yes!!! April Fools Day!!!! Hahaha! I am so excited and can't believe it has been 18 years.

We still are going strong! The press has published books by writers all over the world and I am so happy

to bring you work from so many countries.

Our other big news is that Renuka Raghavan has been named assistant editor of the press. She still

will be doing the beautiful reading and publicity flyers for the press. I am so happy to have her in

this new role with the press.

Since January, we have released 4 books. For April-June, many more books will be released.

Pictured here are our four releases.

You can purchase these books at:

http://www.thelostbookshelf.com/index.html

Bathed in Moonlight by Vassiliki Rapti

Translated from the Greek by Peter Botteas

Video link for Bathed in Moonlight by Vassiliki Rapti, Translated by the Greek by Peter Botteas

https://youtu.be/9CG9-Dx5IkA

|

Saying Goodbye

by Andrew Stancek (Flash-Fiction)

|

Un-Silenced poems by Elizabeth Lund

Video link for UN-SILENCED by Elizabeth Lund

https://youtu.be/CHmRiWwJzB0

|

Heaven with Others

by Barbara Molloy

|

I am planning a poetry and fiction summit for September 30th and October 1st so mark your calendars!

All the presenters will be pre-recording their sessions but the chat will be live.

More details soon on this exciting event!

I will be doing a talk on "Self-esteem and Woman Writers" and "Marketing Made Easy."

Details soon about registering for these.

To celebrate 18 years, there will be many events happening, freebies given, and a

free chapbook or book enclosed with every order starting on April 1st and continuing until June 1st.

The press will pick out the free book. In June, more things will be announced.

I want to give a big shout-out to all my staff for all the work they do. I am so grateful to all of you.

You all are the best! So happy to have you be a part of the press.

Thank you Bill Kelle, Renuka Raghavan, Karen Friedland, Helene Cardona, Andrey Gritsman,

Juri Talvet, Miriam O'Neil, John Wisniewski, John Riley, Susan Tepper, Christopher Riley,

Annie Pluto, Neil Leadbeater, Flavia Cosma, and the late Gene Barry.

Pacific Light by David Mason

Reviewed by John Riley

Red Hen Press, 2022

In Pacific Light, his newest volume of poems, David Mason proves again that he is a poet whose roots

are deep in the mountains and oceans and the time—present, past, and future—they contain. Many of these

poems find a way to know a day placed solidly in the present, only to then remember, again, there is no

present. That there is no life or object, regardless of age or apparent sturdiness, that isn't being

measured in moments.

Mason writes in "Painting the Shed" that the shed

...will surely rot one day

or be blown out by the indifferent god

of a bush fire. Yet it stands, completed

and, like everything else, incomplete.

To know that nothing remains the same is a wisdom that has been around at least since Hesiod or Genesis.

It is also the easiest wisdom to forget, and Mason is a poet that exists, at least partly, to remind us.

"Words for Hermes," the poem placed before "Painting the Shed," begins:

Where will it end?

Night is leaving and it is not night.

The dawn is coming but it is not dawn.

It's something in between. Not yet decided.

This is not to say that the poems in Pacific Light all come from the wise man in the village,

the sage. That they drum drum their way across the page. Any idea, any reminder, is enclosed in

beauty, as though to remind us that awareness and care for the vanishing now is not gloom, that

it may even be the most sublime joy:

Rhapsody in Blue

To say it began at dawn is not quite true.

It began in the struggle of night escaping dreams

when the bounded world encountered infinite space.

Out of doors the shyest creatures moved

under the high holy vault and Milky Way,

bringing their young to the fresh grass, the spring.

In short, the poem is so contained in the beauty of how it tells us what it sees that when it does

return to the "unending sneer and grimace, the demagogue/and the mob" our meditation does not vanish.

The skill needed to both coax us into the moment and to then reveal the destruction of those who fly

blindly from hate to hate is a movement on display in almost every poem.

As a reviewer I inevitably, perhaps, wonder if I should say more and not quote as much. But it is almost

impossible to review this book without being seduced into quoting from poem to poem. What is gained by

writing of the themes of transience and inevitable death and inevitable continuance when the poet has written

of them so well? Pacific Light is a book that the poet apparently views as coming late in a long career. In

the first poem, "On the Shelf," the narrator comes upon the skin of a "huntsman spider" and then remarks:

Perhaps you'll come upon my own shed skins

in houses where my name has been removed...

or find some words of mine in an old book.

I meant them.

It is also a book that deals with events in the poets life-divorce, moving to a distant country with a new

love-and memories of parent's divorce and family death. But these topics are filtered in through the beauty

of the language and imagery and the consolation of time, both infinite and finite. This is why the urge to

quote is so powerful. But I'll stop now and leave it for you to read and feel and have when you pick up

your own copy of Pacific Light.

Split, Twist, Apocalypse by Nina Parmenter

Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2022

Reviewed by Neil Leadbeater

Born and raised in Somerset, England, Nina Parmenter now lives in rural Wiltshire where she divides her

time between writing, work and motherhood. Her poems have been published in numerous journals including

The Honest Ulsterman, Atrium Poetry, Allegro Poetry and Ink, Sweat and Tears. In 2001, she won the Hedgehog

Poetry single poem contest and was nominated for the Forward Prize. 'Split, Twist, Apocalypse' is her

debut collection.

If I had to sum up this collection in one word it would be 'surreal'. In an interview

(Fevers of the Mind, 30 July 2021), Parmenter reveals that she will often put her more troubled or

challenging thoughts slantways into a surreal poem rather than address them directly.

Several poems have an edgy feel to them. In the opening poem, 'Heading to Martock' everything seems to hinge

on the four letter expletive placed strategically in the centre of the poem with a line all to itself.

'Night Rails' reads like a Hopper painting with its memories of early adulthood 'looping / from Coventry to

Castle Cary / destined only ever to change / at Reading'. In 'London Terminal' Parmenter comes up with the

most apposite of words to express or describe a specific moment being 'hot-nosed into a coffee shop / with

the wolfpack.' Faced with being told to mingle with strangers in 'Meanwhile in the Grasmere Conference Suite'

Parmenter offers us a telling description of the shyness that such awkward moments can bring.

We have all been there!

'Tides' is an intriguing list poem that sets out in four numbered stanzas a series of 'recipes for panic'.

The wide-ranging list covers such things as 'objects too close to the face,' 'high heeled shoes,' and the word

'pension' while 'speed, death and tubes' are repeated like a fearful constant throughout the whole poem.

In 'Ease and the Ether' Parmenter imagines herself rising above reality:

Far above the flick-flack of tongues

and the dull tug of duty

I cruise the dewy sky-trails

watching the pedestrians

lessen.

In keeping with several of her poems, Parmenter takes us here, through alliteration and

verbal soundscapes, into a state of otherworldliness.

Several poems are made up out of the vocabulary of body parts: shoulders, hips, skewed vertebrae,

bone, tissue and spleen all get a mention. The human anatomy looms large.

Two poems that particularly caught my attention were the curiously titled 'Upon Reading That You Share 50% Of

Your Genes With Various Fruits and Vegetables' and 'Blooming'. In the former, the opening lines 'Now you understand

/ why you have always felt like a monkey's lunch' set the tone for a poem full of wit and originality.

In the latter, Parmenter treats us to a vocabulary that often surprises, is full of zest, and drives

the poem to an energetic conclusion. Here is the opening stanza:

A celandine went first,

and if we had ever looked, we would have known

it was a freeze-frame of a live firework,

we would have expected

the violence that sparked from the inside out,

the heat pedalling sweetly,

each stamen springing a hellmouth.

Another poem that intrigued me was 'The Committee on Rebuilding Concludes' whose beginning and ending suggest a new genesis for Creation:

And so it is decided:

The hummingbird will paint the sky blue

to show off her plumage, the fox

will stir the earth brown

with his forepaws and brush.

In the stream the minnows will mix shades

of sand and heaven, while the trees

will draw the living green from the sun,

and later, its blush.

....

We don't remember how it was before.

But this seems right.

Whether she is writing about Robin Hood's bower in Longleat Forest, motherhood or photophobia,

rapid eye movement or a walk round Dilton Marsh, in traditional form and in free form,

Parmenter always pleases us with fresh imagery and vocabulary.

Julien Vocance: One Hundred Visions of War, (translated from the French by Alfred Nicol)

Wiseblood Books, 2022.

ISBN: 9781951319373

Reviewed by Miriam O'Neil

Here is Julien Vocance's description of a moment in the trenches during World War I.

Shells come crashing in

shy of our trenches-breakers

that don't reach the shore. (23)

Here is his reality and his translation of that reality-his experience and his way of removing himself from that

experience, at least in retrospect. As Dana Gioia, in his Preface to this translation by Alfred Nicol explains,

unlike those poets of World War I who wrote in "hypnotic [ ] traditional meters" or in "the avant-garde glorification

of violence-with its priapic cannons and flowering explosions" (viii), "Vocance sought clarity not enchantment.

He found a moral stance without any taint of moralism by adopting a radical form into French,

the Japanese haiku...." (viii).

Alfred Nicol explains that, whereas the traditional subject matter and themes of haiku are the nature's beauty,

changes of season, and such, Vocance's adoption of the form to his poems about World War I create a "tension between

the traditional subjects and themes [ ] that serves to heighten the expressive power [of his Visions]" (xi).

And anyone who has seen an even remotely adequate film about the trench warfare of World War I will recognize these images,

such as this brief verbal sketch: "We get a quick look/ around when bursts of gunfire/ light the horizon." (12) is followed

by "Fireworks fill the sky./ Yet another sacrilege/ over these mass graves." (13).

In the nightmare of battle, the natural world has its human imitation when "Black birds in wild flight/ gaining speed,

com[e] this way,/ shells swoop down." (75). Vocance notices the quotidian in the horrific "Blood spilled, washed

with rain,/ muddied, dried...Bright crimson blood,/ so colorless now."(78). And as those horrific images accumulate,

the speaker also moves us from the first experiences of 'rookies' in the trenches, to the nighttime grave digging

for that day's dead, to a field hospital where he notes a patient, "All swaddled in white,/ dressed for the

sarcophagus:/ no hands, feet, or face." (88).

Each set of (mostly) 17 syllable poems placed against the white field of its page enlarges the emotional impact

of that verse, insisting on a kind of lingering, a momentary stay before the next image or scene insists on its

own presence. And, thankfully, as Vocance's one hundred visions arrive at their conclusion, the reader is returned

to the world beyond the trenches, to "The young nun [who] is thrilled/ to have a sketch of Jesus/ the soldier

gave her." (94) and the "consul's wife" who makes her required visit to the hospital coming and going in silence.

Toward the end of this small, sequenced collection, the war begins to take its place in the past, just barely and

we learn that for Vocance, "This is the realm where/ shadows feel their way along/ through an endless night."(98).

In other words, wars end in the world but not within the warriors-there, they may continue for a lifetime.

For all that World War I was conducted along lines of demarcation between armies, it too had all the hallmarks of

a world gone temporarily insane. "Two rows of trenches," wrote Vocance, "Two lines of barb-wire fences:/

Civilization." (102).

In that war there was the surface inference of order and means and something similarly (if insanely) at stake

for both sides, some sense that each government and its representatives on the battlefield and had right on

their side. There was an answer to the question, "Why?". And in looking back, via his "visions," as readers

we survive the horrific and emerge back in the light of our own lamps in our own homes. But now, thinking

about the citizens of this world facing the unsought atrocities of wars and/or persecution waged upon them

in places like Yemen, Myanmar, Ukraine, the Uighurs of Xinjiang Province in China and elsewhere, I wonder

what Vocance would write of their suffering; how would he or could he speak to the involuntary horrors those

citizens face. It seems that in those places, where people wanted only to live their lives in peace,

'the shadows' still insist on feeling their way along. We are more than a century beyond World War I,

the 'war to end all wars,' and we are still in the trenches, still blinding and bloodying, torturing and

killing our fellow beings.

And then there is this-this slim volume of poems written in French in a form borrowed from the Japanese and

translated into yet another language. The poems allow a slow building of impressions. A familiarity we

realize we cannot ignore settles in. It is a small collection of images that asks us to see again and

again, to be cognizant and compassionate and unflinching in our gaze. We need this reminding.

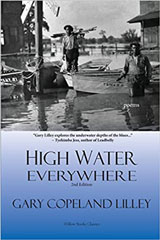

High Water Everywhere by Gary Copeland Lilley

Willow Books, 2022

Reviewed by John Riley

High Water Everywhere is a second edition of one of Gary Lilley's best books. It may even be his best in a list that

includes The Bushman's Medicine Show, a book of poems from the mouth of an everyman who emerges from music to reveal

a life deep in the Southern blues. High Water Everywhere comes from the same place, an actual place in the lowland of

North Carolina's northern Atlantic coast. A mostly rural wet land lying perilously close to the Great Dismal Swap.

In tune with the land and the theme of the book it begins with a flood. But this isn't just any flood. In a series of

prose poems, written in the voices of African Americans native to the soil, Lilley narrates the experience of a flood

that came amidst the slaughtering of hogs. All is slaughter and destruction, which fits deeply into the experiences,

current and historical, of the black families who live there. In "1202 Low Ground Road," a just-so-perfect title, the

narrator starts by lamenting:

Everything gone, birth certificates, the high school diplomas, my grandmother's portrait, the family Bible, everything

that was a record of who we were, gone to fire.

The vicious flood becomes a fire that wipes out documentation not only of the family history but more critically it

destroys the documentation of their very existence. When a people and their family goes through centuries of not being

allowed to own a home, something denied first by the slavery of the master, followed by the slavery of Jim Crow and

the weight of its poverty, the Authentication is not just of property owned, it's documentation of their

very existence.

The second section addresses the black experience a little more directly. At times this is uncomfortable. In the

opening poem, "The Blue Highways," the narrator loses his friendship with a childhood friend named Monk (an allusion to

the jazz great Thelonious Monk, who was from eastern North Carolina) because his daddy kicks Monk's daddies' "ass."

But the heart of the poem is when we learn the narrator and Monk bonded as children because their skin was darker than

most of the other boys. The ever present racism permeates even the people it's directed against.

The final section, "Cape Fear," begins with a note explaining how Lilley learned about the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898.

The label given to the violence, a so-called "Race Riot," came from the men who attacked the black community.

It wasn't a riot, it was a massacre directed by the White Supremacy Campaign that took root at the end of Reconstruction.

The poems, however, are not essays, they vibrate as they narrate how the experience effected those who went through it.

In the poem "The Fire, November 10, 1898," a white supremacy group of two thousand men who called themselves The Red

Shirts, a name that confirms their fascism and is an indication of what will happen in the future, when the hate

consumes the haters, burn down the Charity Hall, where a black newspaper was printed. Finally a "grandmother dropped

to her knees" on the street "in front of the African Methodist church" and "called on her God to destroy these white men."

But God wasn't listening, just as he wasn't listening through all the centuries before, and when the flames move to he

neighborhood school "the colored children broke/from the school screaming and ran through the streets."

The poems in this final section are informed by history, but they are filled with a radiance of experience that can't

come historical records. These are the narrator's relatives, the ancestors of the people who make the poet, and we

are never allowed to forget it. The history that informs High Water Everywhere leads us through the experiences,

the pain, of the people who lived the history. It is a fitting close to a book lifted from the swamps, the

postage stamp of the world the poet knows best. You can read it to learn and leave it to feel.

What more can we ask from poetry?

Office by Susan Isla Tepper

Wilderness House Press, 2022

Reviewed by John Riley

If you didn't live in New York City during the worst of the Covid pandemic it's impossible to know what it was like

there. This is something I realized while reading Office. The book is satire, complete with a boss of a marketing

company who is gone when the book starts but later on builds a tent in the office's reception area and never comes

out of it. There is room for a tent because few people come into the office to work. They say they're working from

home, but there is no work to do. Their biggest client, the one the boss was overly enthusiastic about, makes ear

swabs. Yes, ear swabs. When I first read that I remembered what my ENT told me not very long ago.

NEVER STICK A SWAB IN MY EAR! She's a nice, professional lady but when she warned me away from swabs the look

on her face was probably what her children see when she is frustrated with them. Having swabs be the product

the company is marketing with all their pale enthusiasm is a perfect parallel to life in New York City during

the worst parts of Covid. Everything, absolutely everything, is falling apart.

As in any classic satire, this little book is full of memorable characters. Only the first-person narrator remains

unnamed. There is Quinn, who is of Irish descent although he is a native New Yorker. He talks incessantly about

"returning" to Ireland and has described the potato famine to the narrator in horrid detail. Quinn

spends most of his time preying on women and coming up with money-making schemes. At the beginning

of the book, he tries to set the empty office up as a BNB. It doesn't work. Then there are the women,

Tanya and Stella with beautiful dark hair, who start a "grooming" business, what was once called a beauty

shop, in the front room of the office. They bring in a series of young women to have their hair and make-up

done and in the process, they roll out chaos like a freed car tire flying down a freeway. There's DeGrande,

who comes and goes but is always taking time to sexually harass the women. Kenny is always on the edge of blowing

his top. Other characters come and go, each one playing their roles, but never with subtlety. Everyone and

everything is over the top, as it should be.

The story bounces from one absurd thing to another. It reminded me of Catch 22, the way Joseph Heller drew out

the absurd humor in the tragedy of a senseless war. Tepper manages to portray how Covid rolled through her home

city, killing people with much more efficiency than the Viet Cong, while turning over the lives of those who

survive. If it doesn't kill you it'll make you crazy is what Office reminds us as we settle back into our

"post-Covid" lives and try to return to normalcy. But we now know and can never forget, regardless of how hard we

try, that the world has changed forever. Only a fool, and we know there are plenty of them, can think Covid was

a one-time thing. There is more to come and a book like Office is not going to allow us to forget.

It's a valuable brick in the effort to give clear information and it does that with some of the best satire

I've read in a long time. It does what satire is supposed to do. We laugh and grimace and tell

ourselves we are not like those crazy characters, knowing all along that isn't true. I

suggest you read it if you are ready for a sharp little book that would

hate to see you go.

"Office" is the perfect book for those who made it through Covid with their sanity intact, even if it hangs in

your head a little more loosely than it did before. Read and learn how, as usual, Tepper caught a period of

time and made it hers own."

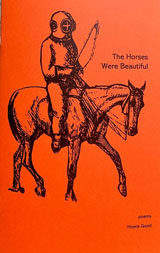

The Horses Were Beautiful by Howie Good

Grey Book Press, 2022

Reviewed by John Riley

I am excited that prose poems are becoming a bigger part of many poets's work. It's not only new poets writing them.

Many of the most heralded poets-Anne Carson comes quickly to mind-use the form. (Carson's "Hegel Says Merry Christmas"

is a brilliant example of prose poetry.) Prose poems often seem to unleash the imagination in ways lineated poems don't.

Obviously, there are exceptions but when I think of the late James Tate and compare his use of the prose form to his

traditional poetry, for example, it's clear that he found freedom outside the line.

Often this freedom comes from how the images are born and die and wrap around other each other, or how the

language pierces through what we expect. This is very often brilliant, but there is room, even a necessity,

for prose poetry that goes in unexpected directions more from the subject and narrative than from the style

and syntax. Poems that allow our the imagination to be engaged in what the poem says as much as how it is said.

Howie Good is an example of a prose poet who uses narrative and the unexpected to surprise us as much as he uses

style. That doesn't mean his style is lacking, but that its his use of both that gives his work its presence.

The Horse Were Beautiful is a bright example of Good at his best. It is a short book that contains many surprises.

In "Stairs To Nowhere," a professor is late for his class. When he dashes into the building and begins up the

stairs "[t]he stairs grew noticeably steeper the higher I climb." At the top, as he gasps for breath, he finds

he had "arrived on the outskirts of a country one only hears about when there is a coup or an earthquake." The

professor, by his own efforts, has left the comfort of middle-class life in the United States and now finds

himself in a place where "a virus crosses the species barrier from animals to humans." Forgive the worn and

weary cliche, but he isn't in Kansas, or Massachusetts, anymore.

"Death Be Not Proud" uses narrated death experiences from Buzzfeed to leave us with the sad reality that even

death can be trashed by popular "journalism." In the three parts of "Re: Vision" a man is fired by

a "gargoyle from HR" and on the street he encounters Jesus who "looked nothing like his picture." Another man

encounters a woman with fangs and a mustache at McDonalds. In other poems, dreams are outlawed, or a man

remembers his birth and that the doctors didn't know how to assemble him. Almost all the poems in

The Horses Were Beautiful take us in these unexpected directions.

Bucharest-born Diana Manole immigrated in 2000 and is now proudly identifying as a hyphenated Romanian-Canadian

scholar, writer, and literary translator. In her home country, she has published nine creative writing books and

earned 14 literary awards. Her recent poetry was published in English and/or in translation in eleven countries,

including the UK, the US, China, France, Spain, and Canada. Praying to a Landed-Immigrant God, her seventh

collection of poems, is forthcoming in 2023 from Grey Borders Books in a dual English-Romanian edition.

Mom loves red.

With love, to all seniors who struggle with senile dementia

She doesn't wear it, she venerates it. She fishes out the

tomato slices from each salad, places them on lace coasters,

and baptises them, using the church calendar-

the bright red ones get names of saints and martyrs, the others what's left,

made-up names without history. She feels sorry for them, but can't help it-

there aren't enough gods for all the tomatoes nor people in the world.

She saves all the cherry pits in a clear plastic bag, zips it, and shakes it,

a made-up tambourine.

"The red sings," she says and moves her shoulders in a chair dance.

Mom asks for apples at each meal but never eats them. She cuts out the peels

and sews them together with silk thread - a necklace! She calls me,

puts the apple peels around my neck-

"Red will protect you of envy and deochi," she winks.

She threads cranberries, raspberries, and strawberries on her drinking straws,

bends them in circles and squares, and then spends hours squaring the circles-

"Mathematics of Berries," reads the label, calligraphed with a trembling hand,

proof that nature knows no impossibilities

where science bows.

When we have watermelon, she carves its flesh with her plastic knife-

"This is you, but prettier," she says, pointing at a juicy lump

with seeds for eyes, a piece of rind for a mouth, and a pointy nose.

"This is your sister when she wore pigtails, this is dad the way

I met him over sixty years ago, and this...Who's this?" she wonders,

gazing at her fourth watermelon sculpture, not recognizing herself.

Mom's dozes off smiling-

a housebound Michelangelo, dreaming of all those who come

to admire her red art show.

Červená Barva Press Staff

Gloria Mindock, Editor & Publisher

Renuka Raghavan, Assistant Editor, Publicity

Flavia Cosma, International Editor

Helene Cardona, Contributing Editor

Andrey Gritsman, Contributing Editor

Juri Talvet, Contributing Editor

Karen Friedland, Interviewer

Miriam O' Neal, Poetry Reviewer

Annie Pluto, Poetry Reviewer

Christopher Reilley, Poetry Reviewer

Susan Tepper, Poetry Reviewer

Neil Leadbeater, Poetry Reviewer

John Riley, Poetry and Fiction Reviewer

William J. Kelle: Webmaster

Gene Barry (In Memoriam)

See you next month!

If you would like to be added to my monthly e-mail newsletter, which gives information on readings,

book signings, contests, workshops, and other related topics...

To subscribe to the newsletter send an email to:

newsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "newsletter" or "subscribe" in the subject line.

To unsubscribe from the newsletter send an email to:

unsubscribenewsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "unsubscribe" in the subject line.

Index |

Bookstore |

Our Staff |

Image Gallery |

Submissions |

Newsletter |

Readings |

Interviews |

Book Reviews |

Workshops |

Fundraising |

Contact |

Links

Copyright @ 2005-2023 ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS - All

Rights Reserved

|