I had so much fun at AWP in Portland, Oregon. I survived the plane ride both ways!!! Thanks to Michael McInnis,

who was a saint, dealing with me on a plane!!! (Of course I had a shot of Whiskey!!!!) Michael and I shared a booth

at the bookfair. He had a beautiful sign made up for our presses, Nixes Mate and Cervena Barva. It was fun hanging

around with him. Michael hosted a reading at his Air B & B for Boston writers and for some of his friends that live

in Portland. We also took part in the Hot Pillow reading. Thank you Joani Reese! Going out to dinner afterwards was great!

So good to see so many writers, editors, and publishers that I knew throughout the days there.

Meeting new people and my new authors was wonderful too. Here are just a few pictures for you to look at.

See everyone in San Antonio next year!!!!!

Teneice Delgado

|

Top: Michael McInnis and Gloria Mindock

Bottom: Joani Reese and Gloria Mindock

|

Lori Desrosiers and Gloria Mindock

|

Gloria Mindock and Ami Kaye

|

Cervena Barva Press has a new series called, Portrait of an Artist & Poet. It has been going great!

So many wonderful writers, musicians, and artists have taken part so far. Renuka Raghavan and Tom Daley kicked off

our series. Since then, we have featured Elizabeth Gordon McKim & Elizabeth Doran, Jennifer Matthews & Peter Urkowitz,

and Andrew Singer & Jessica Purdy.

Renuka Raghavan wrote about a few of them. Thank you Renuka!

Cervena Barva Press hosted our second Portrait of an Artist & Poet series reading. We had a full house!

Gloria Mindock kicked off the evening welcoming everyone and introducing the two featured artists,

Elizabeth Gordon Mckim and Elizabeth Doran.

McKim spoke to the audience of her artistic process, taking inspirations from her surroundings, and the

importance of sound in her poems and art. She mentioned her respect for preverbal communication and how

those sounds are a substructure that connect everyone and everything. McKim shared a few poems, reading

and reciting each with a lyrical vitality that delighted the audience. She invited everyone to flip through

copious pages of journals and work she's done in schools throughout the community. McKim's book, Body India,

embodies her experience as she absorbed the surroundings of being immersed in a new environment. McKim ended

with a poignant and heartfelt poem by poet, Asty.

Doran regaled us with the many opportunities of inspiration that come across her way. She spoke of her work at the

Grolier Poetry Book Shop, and her art: a mixed media approach including collage, hand-written passages, and the

practice of whiting-out. Doran read her poetry and she spoke of the influences she draws upon to create her work,

including but not limited to, Vincent van Gogh, the Wall Street Journal magazine, and even other poets like

Boston-area sound poet, Melissa Silva. Doran read and regaled the audience with a spark of fervent energy that had

people laughing and gasping in awe of her work.

The night ended with a brief Q & A, followed by refreshments and mingling. Thank you to the artists who featured

their work, our intrepid host, Gloria Mindock, and everyone who attended the event!

Cervena Barva Press hosted our third Portrait of an Artist & Poet series reading. It was a great afternoon spent listening

to soulful music and lively poetry! Gloria Mindock kicked off the evening welcoming everyone and introducing the two featured

artists, Jennifer Matthews and Peter Urkowitz.

Jennifer Matthews began her show with a recitation of poem, "Oh Don't, She Said," by Doug Holder. She followed that

by sharing her own lyrical response and then the song she composed out of her lyrical version.

The audience was speechless! She played a few more songs (even taking requests) and then shared her poetry.

Jennifer then spoke to the audience about her song-writing process, how the quiet of night helps create and

compose melody and how much she enjoys waking up in the morning, picking up her guitar and free associating

with melody, harmony, and rhythm. Jennifer also spoke about the freedom of touring and finding inspiration in

landscapes and surroundings. Needless to say, Jennifer had everyone in attendance hanging on her every word!

Peter Urkowitz spoke about the late, Malcom Miller, and the working relationship and friendship they cultivated

after meeting at Salem State University. Peter shared some background information on the documentary,

Unburying Malcom Miller, and shared one of Miller's poems titled, "No More Death," a short, powerful piece that had

audience members gasping. Peter spoke of his artwork, as he is often seen at various North Shore and Boston-area

literary events sketching practically "whoever is in front" of him. Peter even shared the sketch he made of Jennifer

(done within minutes!) who performed just before him. Audience members were treated to beautiful illustrations

of poets like Maya Angelou and Sylvia Plath, as well as Peter's original watercolor works. He ended his reading

by sharing his amusing, Fake Zodiac Signs, a series incorporating Peter's illustrations and poetry.

By Renuka Raghavan

https://www.facebook.com/renukaraghavan/videos/10218800896437606/?t=32

I would like to congratulate Lloyd Schwartz who is Somerville's new Poet Laureate. I am so happy for him!

He will be great for the city of Somerville!

I had a wonderful two years as Poet Laureate and met so many people in the community. It went by fast!

I am excited for Lloyd and look forward to everything he will be doing.

Look for a new series called "Night Riffs" which is a new tri-annual reading/music series founded

by Dzvinia Orlowsky. The first one will be held Saturday, June 1st, 7:30-9:30PM at the Lily Pad in Inman Square.

Info: Brief readings by poets: Dzvinia Orlowsky, series founding director; Betsy Sholl, former Maine

poet laureate; Quintin Collins, an emerging talent; and noted nonfiction and fiction author Kim McLarin;

with a brief interlude of new music by Mischa Salkind-Pearl and Kevin Madison. Join us for gratis treats

and a cash bar while you promote the arts and mingle! ($5.00 cover at the door) RSVP on Facebook.

Congratulations to Karen Friedland on her new book called, Places That Are Gone.

Published by Nixes Mate Publications. It is a beautifully written book so please check it out.

You can order it at: nixesmate.pub

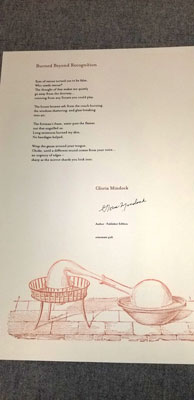

I am so honored to have a broadside published by Nixes Mates Publications. Here it is! My very first broadside so

I am thrilled!!!! Thank you Michael and Annie!!!!

Next month, we will announce our new subscription series. In the past, we had one for the chapbooks.

We have many new ideas to fit every budget for supporting us, so stay tuned.

Cervena Barva Press is an extremely active press. Besides publishing books and chapbooks,

we bring you the following:

- -a poetry and fiction reading series

- -Portrait of an Artist & Poet

- -Pastry with Poets

- -Monlogue Mondays

- -workshops

- -Cervena Barva Press Reads All Over the World

- -Read America Read

- -Poetry Roundtable (founded when I was Poet Laureate and is continuing every other month)

- -Bringing Poetry to the People (founded when I was Poet Laureate and will continue every summer)

- -The Lost Bookshelf Bookstore: selling new and used books of every genre except no children's books,

books on consignment, and some surprises!

What you can look forward to:

- -Translation panels and mini-conferences

- -Translation Roundtable, where selections of a book translation published by Cervena Barva Press

will be read out loud every other month, starting in the fall

As you can see, we offer quite a bit to the community. Some events are free, and some events we charge an

admission. We pride ourselves on offering quality workshops at an affordable price. You should not have to

break the bank to take a workshop!!!!

I would like to thank everyone who has donated books to The Lost Bookshelf. I am so very grateful!!!!

When you look at all the used books we have in the store, it is just amazing!!!! Thank you for your kindness.

All proceeds from the used books go to Cervena Barva Press. In June, I will announce summer hours.

I will try to have a mixture of hours such as a morning, an afternoon and an evening. I will not be

in the bookstore full-time. I will also be glad to open the bookstore by appointment for you if

I know in advance.

Next month, more books will be released! Bill and I have been working hard on them. Exciting!

Big hugs to the Cervena Barva Press staff! OMG!!!!! You are the best!!!

See you next month-

Gloria

Cervena Barva Press Staff:

Gloria Mindock, Editor & Publisher

Flavia Cosma, International Editor (Canada)

Helene Cardona, Contributing Editor

Andrey Gritsman, Contributing Editor

Juri Talvet, Contributing Editor (Estonia)

Tim Suermondt, Poetry Book Reviewer

Pui Ying Wong, Poetry Book Reviewer

Renuka Raghavan, Fiction Book Reviewer

Karen Friedland, Interviewer

Melissa Silva, Promotion

Thank you to David P. Miller for being our guest poetry book reviewer this month.

Please consider making a donation to Cervena Barva Press.

We need funding to survive!

Bad Harvest by Dzvinia Orlowsky

Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon Press, 2018

ISBN 978-0-88748-638-8

Poetry

Review by David P. Miller

Dzvinia Orlowsky's recent collection, Bad Harvest, is exemplary for complex, subtle sequencing, with motifs

that resound across the book. Orlowsky's main themes appear sometimes to take side trips, but always

reverberate - sometimes with sudden coalescences. Although the subject matter takes difficult turns,

eroticism and humor, often mordant, are also much in evidence.

Orlowsky is a Ukrainian American poet and teacher; identity and heritage are significant in Bad Harvest.

These come forward in stories of her parents and family in Ukraine and her life as a child and young adult

in the United States. The stakes are set early in the book, with the prose poems "Playing Opossum" and

"Out of the Woods." The first tells about her parents' attempt to keep the husband out of the Ukrainian army.

The wife tries to deliberately break his leg: "She springs from the horsehair-filled couch,

eyes closed tight, fingers plugging her ears; she lands with a thump. The leg doesn't break." In "Out of the Woods,"

a soldier uncle barely escapes the Nazis by pretending to be dead: "Saved from the dead, gray mold of shallow graves,

he turns over, lips quivering. No soldiers emerging from the woods." These pieces suggest the scope of what Orlowsky

inherits as a child in the parents' new country, as her life takes its own course with stories frequently rueful and

hilarious. "Electric Lady" tells about her single night as switchboard operator at the famous Greenwich Village

recording studio. No actual details about this fiasco are revealed, but final questions suggest that proximity to

famous men might not have been as delightful as imagined: "Female jacks? Trunk lines? How hard could it be?"

"Napoleonic Series, 1974" presents her as intern for the artist Agnes Denes, who in this work inked penis

imprints onto graph paper (http://www.tonkonow.com/carnalknowledge3.html). The artist seems to expect that

"her project would shock me all the way back to Ohio," but Orlowsky was equal to the challenge: "it wasn't

what you'd call boner-worthy." However, the generational tale remains complicated. In "Fack You," the father

is shocked at language overheard from his daughters' mouths as they play ping-pong in the basement:

Have either of you heard of the word … "fack?" He pronounced it like he pronounced "mashrooms"-immigrant doctor

ordering pizza at Fatbob's when Mother came up short on chicken livers or tripe. He looked at us in disbelief,

his now foul-mouthed daughters.

As an instance of the collection's mosaic nature, "Fack You" is preceded by "At the End of Your Life."

The mother, not particularly entertained by an Elvis impersonator in the Life Care Nursing Home,

receives an ambiguous treat:

You eat the neon-colored frosting cupcake the nurse's aid offers to you, allow sugar to settle between

your teeth. But this is not you, not your style. Where is your pastel portrait drawn on black construction

paper, your hair wild as radish roots, eyes with dark circles, as those on potatoes?

And the generational story spins out still further, with "Let the Dead Bury the Dead." Here it gradually

appears that the deceased father tries to imagine what he could or should do for his dead wife; except

that he can't: "Maybe he wouldn't need to bring his guitar, just his hands, if he could remember where

he last placed them. Except, also, that she "was still very much alive. Night after night she stood in

front of the bathroom mirror, brushing back her filaments of fine hair." Details of their lives,

his uncertainties and insecurities, fold into a mirror game of baffled tenderness and disconnection.

This is a strong and poignant poem about what long-time couples share, even in its sometimes brokenness.

The pieces cited so far belong the first of Bad Harvest's three parts. The second begins with the

title poem, a sequence. In stark contrast with the first section's prose poems, the seven poems of

"Bad Harvest" are brief, with as few as four and no more than seven lines. They respond to the

Ukrainian famine of 1932-33, Stalin's work, in which as many as seven million Ukrainians died.

The magnitude of this disaster is evoked by miniatures, where what little is said suggests the

extent of what is not (and indeed personal silence and official denial reigned for decades).

Here is the complete text of "Want":

Come out we have a doll for you

neighbors disguised-kindly,

not succumbing.

Never open the door.

If the suggestion of cannibalism is not clear enough to the reader, one may turn to the poem immediately

following "Bad Harvest," titled "The Weakest of Children."

Where the "Bad Harvest" sequence throws us into a background of catastrophe, against which we may

reread the familial, autobiographical first section, the second concludes with "Kalendar," vignettes

titled with names of months in the old Ukrainian language. "Kalendar" parallels "Bad Harvest"

in compactness of expression, and counters modern political slaughter with the deeper cultural

knowledge embedded in language. Some vignettes speak directly to an elemental part of the season,

as "sichen? - to slash" (January) addresses the wind: "do you use a scalpel / so precise, // it cleaves /

life-death's infinitesimal point, // the soul released / for its journey?" Others reflect on particular

experiences associated with an element: May's "traven? - greening of grass" says "Blade of grass,

cut our lips - // Tight between our thumbs / we try to make you sing." In between the brackets of

"Bad Harvest" and "Kalendar," other poems in the book's second part further address matters of

inheritance. Examples include "Losing My First Language" (discussed below) and "Inventory," which

brings forward the generation of the poet's grandfather, particularly through his "hand-carved chess

set … the king's crown / a bent nail, // the knight's horse / a nub on a pedestal // robbed of wings".

Braided allusions to unspeakability, or speech against silencing, run throughout Bad Harvest. The

title sequence has an epigraph from The Ukrainian Weekly, in reference to the famine:

"Even if it was mentioned, it was one sentence …". The copious white space on each page of

this sequence's poems provide respectful frames for its laconic utterances of horror and

conceal the rest of what might be said beneath their blankness. What cannot be spoken is

complemented in other poems by the inability to speak or mockery of the spoken.

"Losing My First Language" evokes the loss of knowledge as the use of language decays over

generations: "Where / is the language of the nightingale, // of the child who received /

the song of Ukraine when Saint / Nikolai ran out of toys?" This sense of cultural precarity

stands in contrast with the confidence of "Kalendar," and is complemented by "Our Names," a

poem testifying to a dominant culture's refusal to honor the most basic element of a name,

its pronunciation:

Our names tagged

as liars, out of control fires,

reinforced with wires, twisted

into barbs with pliers, claimed,

maimed-who put the blame on

the lame that spewed from us?

The poem's playfulness of rhythm and internal rhyme is belied by assertions that these names - critical

signifiers of heritage and identity - must somehow be unpronounceable, un-American, alien.

The unseen twins the unsaid, as evoked in "Invisible Departures," with a headnote referring to "internally

displaced persons, Crimea, 2015": "How silent the instrument / that comes down like a hammer //

one someone leaving, / someplace left." Note that "how silent" does not initiate an (unanswerable)

question, but evokes something unmeasurable, as do "how long" and "how swollen" earlier in the poem.

Orlowsky treats the matter of what is tabooed or shut away with humor as well, particularly in poems

in the book's first section. The father's struggle in "Fack You" is precisely with his daughters'

forbidden speech. "Bare-Assed Hell" and "Why I Hate Nudist Camps," both hilarious and discussed

further below, verge on Too Much Information. This reader is both fascinated by and a little uneasy

with these revelations; visualizing the scenes, he wants to read/not read as a complement to look/not

look. But the most audacious instance of breaching the unspeakable is "Lord Taylor,"

which poem parodies Carolyn Forché's well-known poem "The Colonel" - parody in the technical,

not satirical sense. Documenting atrocities in 1970s El Salvador, Forché experiences the following

in the home of an army officer: "The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries / home.

He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like / dried peach halves." He mocks, "Something

for your poetry, no?" In "Lord Taylor," the poet as young woman makes her first sale of jewelry

in a high-end department store:

Adjusting his tie, leaning closer to me, Lord Taylor asked how did it feel making the first sale.

He spilled out bags of hoop earrings. Something for your commission, no?" The nearly outrageous

parallels (and there are many) are almost too much to laugh about. But one does, while punctured

with an even stronger sense of our own insulation from the silencing of atrocity victims.

(At least, comparative insulation, so far.)

Physical fragility, as a mirror of cultural collapse, is also present in these poems. The title

sequence's catastrophe of famine and cannibalism resonates with the failed attempt to break the

father's leg in "Playing Opossum." The parents, healthy and vigorous in the latter poem, reappear

later in their decline and decease. In "Glue Wind," which opens the book's third part, the

speaker expresses a complex relationship with artwork left by Tamara, a deceased, elderly artist.

Details of Tamara's story - her age, widowhood, probable existence as Holocaust survivor -

come out almost as side comments. They intermingle with an ambivalent attachment to a seemingly

awkward painting made of Elmer's Glue, needed as memory, perhaps less needed as art:

I suddenly want to take it down from the wall,

as if to say once and for all: glue is glue,

others have done it. Though maybe not

with her 85-year-old arthritic hands.

[…]

Maybe,

even though I know it's just glue

and not the winter wind, every December

I'll return the painting back to its place

next to the window wall

where I can look at it while I eat […]

Three other poems in this part approach the flesh from different perspectives, like facets.

"Fine Despite" fuses exuberance and the experience of chemotherapy:

"I haven't felt so alive in years! / At least that's what you're supposed //

to say when you've had cancer. / I don't want to let fellow club members down:

/ I'm riding shotgun with a shooting star. / I'm demanding my eighth-grade picture

be retaken." The title, "Age of Osteo Collosus," is an interesting puzzle. Spell

check doesn't recognize "Collosus" and online search results insist on "colossus,"

so for now I'm taking it as a portmanteau of "porosis" with "colossal." Regardless,

the poem replaces the edgy humor of "Fine Despite" with relentless images of the body

in a state of near-crumble: "pumice stone, partial / knee, rubble swan neck, / taxidermied

hummingbird, // tumbling twigs, tumbleweed / joints". The book's penultimate poem,

"Separate Bodies," returns to the father, his vulnerability now echoed in the poet's body:

Drug-punctuated veins, hands resting,

driving, not admitting to be tired,

we've taken on similar illnesses: sandbag face,

trees burning in each other's dreams.

[ … ]

I was always listening, always there.

I've stopped listening.

But tell me there is more

than the color of our eyes.

I've repeatedly alluded to the dark and hilarious humor Orlowsky brings to many of the poems in

this book. Laughter, sometimes uneasy, rueful or compassionate, mates with the carnal, complements

the pain of physical decay. Humor addresses a range of unsettled, not quite locatable affects. In

addition to poems already cited, "Bare-Assed Hell" must be mentioned as a place where laughter

meets the almost unspeakable. The girl Orlowsky and her sister, as punishment for fighting, are

forced by their mother to sit, with naked nether regions, on each other's bed pillows for twenty

minutes:

Truth be told, I was concerned about the welfare of my behind. No matter how primly and properly

we were raised, chances were that we both sweated and drooled in our sleep. On what, exactly,

would I be sitting?

This reader, at least, reacts with can't look, can't not look, don't picture it, but can't help it,

since after all it's right there on the page and it's funny. We're given an adult take on

attraction/repulsion comedy with "Why I Hate Nudist Camps." Here the speaker, in a relationship headed

for wreckage, is in a grown-up situation as queasily erotic as can be, where every opportunity to

celebrate the flesh turns against itself. Given, for example:

the other "campers" at the Get Down Hoe Down, pot bellies split with Caesarean scars,

squash-shaped sagging breasts swaying joyfully, or that group sportin' softies at the

Mister Softie Machine.

This complex and fascinating collection is noteworthy also for the thoughtful design of

its section designations. Roman numerals are used, nothing unusual in itself, but here

developed as graphic design elements. Gray columns, they absorb title page numerals and

stand nearly mute on section break pages (echoing the motif of what is unspoken). It is

possible not even to notice them as Roman numerals, but this reader couldn't help but see

them as twin towers heralding the disaster of the second section's title sequence.

This review has left many fine poems undiscussed, so to conclude let's say: Dear readers,

all this and much more in only seventy-nine page. Dzvinia Orlowsky's Bad Harvest is highly

recommended.

Interviewed by a Cervena Barva Press Intern

(Please note: No credit is given to the person who asked the questions.

Sorry…I will keep trying to find out who did this because I want the past intern to have credit.)

Do you have a favorite book of poems you can always enjoy reading over and over? Do you have a favorite author or genre of writing?

I've probably read Galway Kinnell's Book of Nightmares at least once a year for a dozen years. His poems there mesmerized me,

moved me, inspired me. My paperback copy is all marked up and full of marginalia. One of my former high school students and I

talked quite a bit about Kinnell's achievements in that book, so much so that he found a first edition hard cover of it and

held onto it several years until Kinnell gave a reading in his area in Vermont, with the intention of having it autographed

for me. He gifted me with the inscribed copy on my fortieth birthday. One of the best gifts I have ever received

(thank you, again, Greg!).

At different times in my life, different poets/poems meant a lot and I would read/re-read them. They are too many to

mention here, but Rexroth, Rilke, and Roethke were very influential (and that's just the R's). Two long poems that touched

me and taught me quite a bit about poetry when I was young and just beginning to think seriously about writing poetry

are Allen Ginsburg's "Howl" and T. S. Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," very different poles to navigate,

very different pools to wade and not drown.

A current book I am reading is the new biography of Giambattista Bodoni, the eighteen-century Italian printer and

typographer, whose name-sake type font became very popular in the twentieth-century. I've read a lot about the

history of printing and the development of type. I'm also passionate about fly-fishing for trout and fly

tying, so I read a bit about that. On my reading table is John Gierach's All Fishermen Are Liars, his

newer collection of essays chronicling his adventures on the rivers. That's next. Beneath that is the

selected letters of the poet Anthony Hecht, which I dip into now and then.

Hecht was a master and probably the most sonorous reader I've heard. I was in Hecht's workshop at the

Bread Loaf Writers' Conference back in the mid 70s and we corresponded briefly afterward; two of his

letters to me are included in the volume. For relaxing reading, I enjoy detective novels, Robert B. Parker.

Sue Grafton. Sometimes it's good to just dive into a relatively meaningless yet enjoyable

story and these two writers fit that bill. All these, of course, are in addition to the many,

many books of contemporary poetry that I buy or are sent to me. Beneath the Gierach is classics

scholar David West's Shakespeare's Sonnets, a very exact though not quite academic exegesis of

each sonnet. Also next is the Letters of John Lennon (I'm a huge fan of The Beatles and have a

book shelf of titles about them). And after that….

Does being editor and publisher of Adastra Press help you in your own writing? Because you read and

publish other people's poems, have you learned about ways to improve your own poetry at the same time?

Being an editor exposes one to a wide range of poetry: styles, themes, voices, coming across your desk, your

imagination. The majority of these are poorly written, cheaply thought-out. This helps an editor cement his/her

own definition and criteria for what makes a good poem. This alone, seeing what not to do, aids in

writing one's own poetry. Reading and sometimes editing others' poetry for 39 years has certainly

broaden my vision of poetry and influenced my writing in that way, more than any specifics.

Since almost all editors are writers themselves, it is too easy for them to be directly influenced

by the writers they publish. Younger, beginning editors probably are. They shouldn't be, other than aesthetically.

All editors have their own biases that developed from their reading, their schooling, their mentors,

and their life experiences. Fair enough. But they should know that it is the editors, themselves,

in the act of selecting for publication, who establish what good writing is. If the editor does not

have a firm grip on their own definition of good writing, then what they publish may not be as

good as it should be. If the editor does not highly value good writing, then what they publish

will have less value. Though the meanings of "good" and "value" as regards literature naturally

change over time, there are some constants. "Truth is Beauty, Beauty is Truth" as Keats wrote

still applies. Creative writing that attempts at a truth invigorates a reader; creative writing

imbued with the beauty of language, image, metaphor instills within a reader the desire to laugh,

cry, dance, shout at the clouds; creative writing that stretches the use and function of language

expands human experience. Homer is still widely read today, as is Shakespeare. Only English

majors read Milton today, and with good reason.

If every editor of a magazine accepted each piece of writing with the idea that that story, poem,

or essay is a part of the definition of good writing, then literary journals would be more readable,

though thinner. If every editor of a press included in each book they published only those poems,

stories, essays that convey the definition of good writing, the results would be more satisfying,

though, again, the volumes probably much thinner.

It's pretty neat that you hand-make books with a letterpress. When did you start learning about

printing books that way? Does it feel like a bigger personal connection with the poetry when

you make chapbooks by hand?

My first couple of poetry chapbooks came out during the end of the mimeo revolution of the 60s,

70s, early 80s. That was a time period when the corporate publishers were a fairly closed market

with a very limited definition of what a good poem looked and sounded like. During this revolution,

the writers, themselves, formed groups to become their own editors and publishers, to take away

the power from the corporate publishing houses. Not having corporate financial resources, they

published magazines and chapbooks as cheaply and quickly as possible, which meant using typewriter

type setting, spirit duplicators and mimeograph machines for printing on cheap copy paper with

stapled bindings. It was wonderful to see our writing in print, even if the quality was more

amateurish than professional. After doing research on book-making history and visiting the

rare book room at Smith College, I came to the conclusion that poetry deserved a better

face than stapled mimeograph. I took a night course in graphic arts at the local

vocational high school, from hand set metal type and letterpress printing to computer

generated type, camera work, and offset printing, and did a letterpress chapbook of my

own poems as my class project. That was the beginnings of Adastra Press. I used my own

poems as the experimental model to see if I could do it and I could, so I did.

It is a magical experience to hold the words of a poem in your hand one letter at a time,

to actually assemble those words. Each letter has its own literal weight just as the words

of a good poem have metaphoric weight.

If the poet whose book I'm working on lives within a day's drive, I invite them to the press

to help in the physical making of their own book. Every one of these poets, regardless of their

age or reputation, always goes away from this with an entirely new perspective on the making of

a poem and a book of poems. Several of them have written poems about it. Three of them became

apprentices to learn about letterpress printing and two of them established their own presses.

But here's the anxiety I have about the entire process: I worry that I may be putting into a chapbook

more effort, more sweat than the poet did. I've turned this fear into part of the editorial process of

accepting manuscripts. It takes roughly eighty hours of physical labor to turn a sixteen to twenty-page

manuscript into a finished chapbook: typesetting, printing, sewing & binding. I want the poems to show me

in the reading of them that the poet put at least that much mental labor into their poems. This is

impossible to judge, of course. But as a poet myself, I also know what goes into making a good poem.

So I try to balance this dual awareness into selecting work that reflects both labors, that does honor

to both efforts.

More recently, say in the past eight or so years, another element had entered into my selection process.

During this time, I noticed that I had been subconsciously accepting manuscripts that not only fit the

above criteria but also contained physical poems and themes which challenged my book design and book

making skills. If I had narrowed my choice down three manuscripts and could only take on one, for

example, I actually chose the one that would stretch my skills as a book designer/maker, that

would challenge me graphically. I have been very satisfied with this discovery because I believe

my abilities have increased and the product is more attractive than ever.

And now, after 39 years and 115 titles of broadsides, books, and mostly chapbooks,

by fifty-eight poets from across the country, I am bringing Adastra Press to a close,

with one more title to print and publish in late 2019. I began the press with a group

of my own poems as an experiential test of my book-making, and after publishing such

poets as Michael Casey, Jim Daniels, W.D. Ehrhart, Thomas Lux, Ed Ochester, Tom Sexton,

and Laurel Speer, I will come full circle and conclude with my own poems.

Do you go back sooner and edit your own poetry by line and organization, or do you just let

it write itself out and then go back later?

I write mostly by inspiration, meaning, I have no regular writing routine. When a poem comes,

I generally let it fester in my head until it forces its way out. Sometimes, I get so moved by an

idea, sight, a read or overheard phrase, that I just begin writing and let what happens develop

itself. In such instances, I try to write it all out then go over it right then or the next day

or the next month, depending on how certain I feel about the piece. The worst part of the process

for me is when I'm furiously writing, say up to line twenty-three when I realize I used the same

word, especially when it is an adjective, that I wrote in line two. I'll stop and reconsider both

usages, find alternatives, or if I can't right then, I'll mark it and go back later. Sometimes,

and this is the part I hate, I get so hung up on this that the poem doesn't get finished. I put

it in a folder in a desk drawer where it joins all the other failed or unfinished poems. Sometimes

I take out the folder and read through the sheets of paper. Every now and then, I'm able to rescue

one of those lost boys and bring him into adulthood. They never regret it because they know that

even Peter Pan secretly wants to grow up, wants to become whole.

A poem in the new book, "Goshen Stone," wrote itself out for the first fourteen lines that describe

finishing up a job laying a stone wall. I know the process well, having been the helper for my father,

a plasterer, bricklayer, stone mason. I just closed my eyes and remembered my father at one specific

job. Everything went exceeding well up to that point. But then I realized I didn't really know what

the poem, itself, meant, or where it was going, or should go. It ended up in a folder of unfinished

poems. A few years later as I was flipping through those loose pages, I reread it and realized I was

writing a family heritage, that it was really about my son, what he needed to know about his father

and grandfather, and quickly completed the poem, with later minor adjustments to word choice and line

break. It's one of my favorite poems in this book.

Another example: The final poem in the new book, "At the Window," was simple in origin: while reading

in bed late one summer night, the sound of something bumping into the window screen had been going on

for an hour or more, becoming a distraction from the reading until it became an irritation to the point

where I couldn't keep focused on the book's train of thought. So I got up from bed, raised the blind,

and was startled to see myself reflected in the shiny night-black window glass. This passed quickly as

the bumping resumed. Then I focused on some moth flying, smashing into the window screen, several at a

time, inch-long bodies with tan wings fluttering unceasingly, with one stuck into the screen's webbing.

I took a closer look and could see the insect's claws looped through the tiny mess openings, stuck there,

with wings beating furiously. I couldn't tell if it was trying to escape or break through the screen to

get at the source of the light. All these mixed ideas of motivation and self-reflection began swirling

in me and I took up the blank journal I keep on the nightstand but didn't know where to begin. So I

simply stated, "A moth at the window." Not even a complete sentence, just a phrase naming the moment.

Descriptive phrases followed merely to explain the situation. Then I went deeper, speculating on this

clash of the natural world and the human world, which led to questioning the very essence of windows

in our homes, our lives. From there into comparing what an insect cannot know and what humans cannot

know. We've all found dead insects, dead moths. Their dried-up, stiff little bodies lying on the ground.

Since these simple little lives are driven by reproductive instinct, whereas all of human history is an

attempt to deny or control that same instinct in us even though we've romanticized it all as love,

elevated it all above mere sex, those are still powerful motivations. I end the poem with that simple

speculative question in what I think is one of my best ever last lines: "stiff with ecstasy," which, of course,

is an attempt to transpose human emotions unto sense-less and emotion-less creatures. All this backstory is

much more complicated than the surface thinking and level of language employed in the poem, itself, which

is as it should be. That's why it is poetry and not an essay. At any event, this is how I see this poem's

making and its "history." I chose to close this book with this poem because it is a literal example of the

book's title: Captive in the Here, with both the moth and the person a hostage of the moment. Whew. I'd

rather just read the poem than try to "explain" it. But I hope readers will get some of this, for any

decent poem, on their own.

I could probably give a short "history" for each poem in the book, as I'm sure most poets can for their

books. There is so much emotional and intellectual weight in the writing that the process often becomes

etched in our imagination, as it probably should. Do I think Renoir didn't recall the situation or

motivation of his Luncheon of the Boating Party, or Gustav Mahler the composing of his Symphony #5?

Whether or not the individual artist or poet is cognitively aware of it, is able or willing to talk

or write about the origin and process of any given work of art, it is imbedded deep within the psyche

of the creator.

Just for fun: Do you like snowy weather? What is your favorite color?

I love snow. I love walking in it, shoveling it, snow-blowing it, and simply watching it fall onto the

hayfield behind my house, pile up about the shrubs around my house, fill the tree branches with frozen

blossoms. When snow is falling that is a time for quiet contemplation, for meditation. I taught high

school in western Massachusetts for thirty-one years and the school averaged five snow-days a year but

double that some years. In winter the kids dreamed of snow days and most teachers prayed for snow days.

On the lounge chair in my living room is a small blue pillow my wife bought me that is bordered in

white with a white snowflake in the upper right corner and in the center the phrase, "Let It Snow."

She understands. She knows. In summer, I turn the pillow over to just the plain blue backside, but

I know what is embroidered on its front. Also, as I extended my fly fishing into the winter, I've

grown to love standing in moving, frigid water, casting an artificial fly into the unknown as snow

begins to fall, twirl and swirl around me. It's a simplistic, black and white world. And suddenly,

you pull a beautifully colorful rainbow trout out of that dark water. Ah, mystical. I wish I could

say that the pinkish stripe along a rainbow trout's side was my favorite color, but it's not. Blue

is, especially midnight blue.

If you would like to be added to my monthly e-mail newsletter, which gives information on readings,

book signings, contests, workshops, and other related topics...

To subscribe to the newsletter send an email to:

newsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "newsletter" or "subscribe" in the subject line.

To unsubscribe from the newsletter send an email to:

unsubscribenewsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "unsubscribe" in the subject line.

Index |

Bookstore |

Our Staff |

Image Gallery |

Submissions |

Newsletter |

Readings |

Interviews |

Book Reviews |

Workshops |

Fundraising |

Contact |

Links

Copyright © 2005-2019 ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS - All

Rights Reserved