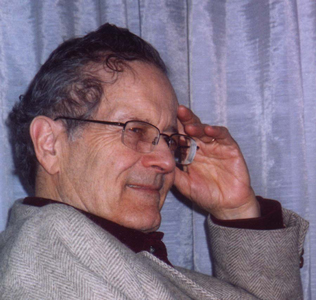

INTERVIEW WITH DAVID RAY BY SUSAN TEPPER

About David Ray

DAVID RAY's latest book is Music of Time: Selected and New Poems. Some of his previous volumes are:

The Death of Sardanapalus and Other Poems of the Iraq Wars; One Thousand Years: Poems About the Holocaust; Demons In The Diner;

Kangaroo Paws, Wool Highways, and Sam's Book. He is also author of The Endless Search: A Memoir which was praised by

Robert Coles as "a story of childhood vulnerability become, in the hands of a gifted, knowing poet and essayist, the

stirring reason for a lyrically expressive memoir."

David Ray has received awards for his writing, including the William Carlos Williams Award from the

Poetry Society of America, the Maurice English Poetry Award, the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation Poetry Award,

and many others. He has taught at universities in the U.S. and abroad, and was founding editor of New Letters magazine

and New Letters on the Air radio program. He has also edited several anthologies and often presented readings and workshops.

He lives in Tucson, and can be reached at http://www.davidraypoet.com

NEW: Music of Time: Selected & New Poems

(The Backwaters Press, 2006.)

http://www.davidraypoet.com

djray@gainbroadband.com

LET'S DIVE RIGHT IN AND DISCUSS YOUR BOOK "ONE THOUSAND YEARS: POEMS ABOUT THE HOLOCAUST." WHAT BROUGHT THIS BOOK TO LIFE?

I've thought about the Holocaust for years, partly to remedy my ignorance, which I was made aware of only after my

University of Chicago classmates challenged those of us from the Midwest who were, in effect, judged guilty not only of

ignorance but of callousness. I was recently reminded of that naiveté when the future King of England foolishly donned

Nazi armbands and threw a Mel Brooks mock Heil Hitler salute. I'm sure he had no idea what he was doing other than

cavorting, but to summon Holocaust images under any circumstances justifiably provokes outrage.

Another example of this kind of naiveté was the recent caper at Prospero's Books in Kansas City when the owners

staged a sidewalk book burning to protest the lack of interest in books, the fact that they could not even give

away the thousands volumes of overstock, yet some passersby were plucking books out of the flames. They foolishly

if unwittingly summoned up, as if cursed by Prospero's storm-making, ship-wrecking magic, a Holocaust image.

Not smart!

But my main reason for writing the One Thousand Years: Poems About the Holocaust was my own suffering, childhood

trauma so extensive that it was a sentence to suicidal attempts and a lifetime of therapy. To dwarf such pain

with attention diverted to those who suffered far greater horrors helped put my pain in perspective.

(Yes, writing is therapeutic, let's settle that question, at least for me, not Sylvia Plath or Virginia Woolf.)

To some extent such catharsis is life-supporting, though it has the downside of dredging up pain as well as

seeking solace. The same is true of most of my work, certainly "A Hill in Oklahoma," a poem about my parents

during their hardscrabble days in the Great Depression (and it was a Great one). It is true of Sam's Book,

which expresses the tip of the iceberg of my grief experience. As those who have lost children can tell you,

there is no greater pain, short of a Holocaust like Hitler's.

Someone commented that all my poetry seems to be about victims, and that's true, whether in a poem from

Dragging the Main about the waitress denied dialysis for lack of money or in those about Vietnamese peasants,

homeless people, children of Baghdad or Bhopal -- or Berlin, the children Hitler took on his knee in

"A Song for Herr Hitler," then sent them to die for his follies. A list of the various kinds of victims

in my work would be very long. It is presently lengthened by concern with those who, in the ritual

called capital punishment, are killed by the state, and by 'illegal immigrants' dying in the desert for

lack of a compassionate immigration policy in tune with our ideals.

As for abandoning our ideals by giving way to corporate and government betrayals as well as our own

acquisitive habits, Juliet B. Schor, in The Overspent American, has much to say about this betrayal of

Communitas. The book's cover is inspired by Grant Wood's American Gothic: the farmer's pitchfork is now

a golf club and his wife stands beside him in dark glasses, scarlet lipstick, low-cut blouse and three

strings of pearls, a cup of Starbuck java in her hand. Both she and her husband hold cell phones to their

ears and behind them their gothic-windowed no doubt refurbished house sports a satellite antenna.

Schor, following Thoreau's advice to simplify, attributes downshifting to "millions of Americans recognizing

that in fact their lives are no longer in synch with their values… Downshifting involves soul-searching and

a coming to consciousness about a life that may well have been on automatic pilot." I would add that poetry

is soul-searching. We write from grief, grief never ending because holocausts keep happening on all continents.

From One Thousand Years:

ECOLALIA

Europe bleeds again.

I am old enough to know

it promised not to.

The betrayal of ideals destroys our bliss, and each day is suffered as if we are forbidden ever to see rainbows again.

A book about the Holocaust should remind us that we should hold to our ideals at any cost, honoring Kant's categorical

imperative. There is unremitting sadness in knowing that the world is endangered by every weapon on earth and by our own

toxicity. When we lived on a farm in Calabria my daughter Wesley picked up a reminder that old evil burns on like the

radiation from Hiroshima and thousands of bomb "tests," preparation for future holocausts.

A PIECE OF SHRAPNEL

The Rock That Doesn't Break, she calls

it that, picks it up in a field of clover,

brushes off the mud, asks me what it is,

but who am I to explain war to a five-

year-old, who myself see something which

even to touch is dangerous, it is so sharp

and unshiny. I can feel it wanting

to hurt, to whizz through the air, land

in a tangle, be sold and resold. I can feel

how restless it is, not having found after

all this search a grave, where it can rest

and not be picked up, once more estranged,

plowing again through hands and delicate

faces. It is like a small, tired heart

begging not to be stolen still again from

this grave, which is in a field of clover.

Gathering Firewood and Music of Time

Thinking of such matters, I made another observation:

IN HELL

all journeys seem longer

images sharp, as you meant them to be

in heaven.

Gathering Firewood

That poem's another of my shorties. I've loved the term since May Sarton wrote me that she loved

my shorties. I'll give her credit, and thanks, for the neologism.

What would it take to have hope for heaven as well as hell? Robert Frost seemed to think there's

even hope for the past. Imagine, finding hope despite such horrors as the Holocaust, a presumably

noble quest of questionable morality even to think of it. Mr. Frost, we can forgive our own crimes,

but not those of others.

THANKS, ROBERT FROST

Do you have hope for the future?

someone asked Robert Frost, toward the end.

Yes, and even for the past, he replied,

that it will turn out to have been all right

for what it was, something we can accept,

mistakes made by the selves we had to be,

not able to be, perhaps, what we wished,

or what looking back half the time it seems

we could so easily have been, or ought…

The future, yes, and even for the past,

that it will become something we can bear.

And I too, and my children, so I hope,

will recall as not too heavy the tug

of those albatrosses I sadly placed

upon their tender necks. Hope for the past,

yes, old Frost, your words provide that courage,

and it brings strange peace that itself passes

into past, easier to bear because

you said it, rather casually, as snow

went on falling in Vermont years ago.

Sam's Book and Music of Time

No matter how regrettably our "creative" intentions misfire, taking action is more honorable than evasion and paralysis.

I stray from your question, but that's precisely what my writings do, whatever scattered work you mention.

I hope my leadings of conscience, especially One Thousand Years and The Death of Sardanapalus, will not be

remembered merely as propaganda. I hope I will not, like Cervantes, wind up burning my manuscripts. I hope

I will not, like Flaubert and Tolstoy, curse my work as contemptible. I hope I will not, like Edna St. Vincent Millay,

depressed and addicted to alcohol and morphine, denounce as "propaganda" her work of humanitarian passion such as

The Murder of Lidice and her activism protesting the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. Did she really want to be

remembered only for her sonnets and that splendid poem of enthusiasm for nature, "Renascence," which made her famous

while she was still in her teens? Instead, I would rather witness, in all senses of the word, to the unbearable

lightness of being, not the unbearable burden of darkness.

When one's work finds a single reader who really grasps that work, regardless of its rasa (Sanskrit for the various aesthetic modes)

all the struggle seems worth it. Perhaps, Mr. Frost, that's hope for the past. Occasionally a single reader finds you,

saying he found your book on a dusty lower shelf. (I think of E.A. Robinson's poem, "Crabb") A woman writes that one

of your poems made her weep every time she turns to it. Another writes for permission to read one of your elegies at a

funeral or other service. Another wants to reprint "Thanks, Robert Frost." Yet another, a composer who ran across

Sam's Book, asked permission to set my poems to music. He wound up composing music for my transcreation of a poem nearly

every Korean can recite from memory,"Azaleas." Such contact creates an instant I-Thou relationship.

One of my I-Thou relationships was with David Ignatow, who in a jacket statement for Gathering Firewood contributed

the truest insight that could be said of me and my work: "David Ray writes poems that are like a man with an injured

child in his arms walking from street to street in search of a doctor or a hospital. He finds none and keeps walking

doggedly, and we may tell him, David, such a cure you are looking for for your injured faith in the world is in the

truth of your poems. They will survive, they will survive."

Robert Hass writes that "the first impulse of any art is, no doubt, to make something, to act on the world."

He quotes Denise Levertov: "We are the humans… whose language imagines mercy,/ lovingkindness…" For all the faults

and flaws of my work, mercy and lovingkindness is all I've aspired to share. If only we could press those values into

action with the same enthusiasm others give to war!

IN 1966 YOU EDITED (WITH ROBERT BLY) "A POETRY READING AGAINST THE VIETNAM WAR." YOU CONTINUE TO WRITE PROLIFICALLY AGAINST

ALL WAR. ARE THESE WRITINGS FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF ONE WHO HAS BEEN IN A WAR, OR ESCAPED THAT HORROR?

First of all, I think that a position against war, though you have no more been there than Stephen Crane when he penned

The Red Badge of Courage, can be as valid as the opinion of one who has waded through the blood of battle. A stance against

war may derive from greater, not less, moral clarity, more knowledge of the lessons of history, and compassion for the world.

A warrior, understandably, for tons of propaganda will have been aimed at him, may become indoctrinated with the conviction

that the sacrifices demanded are worth it even if, in fact, the lives of his comrades were simply thrown away by the arrogance

and hubris of their leaders.

When Robert Bly and I started American Writers Against the War and stimulated efforts of poets to stop the Vietnam war we

sometimes had our lives threatened, at least I did. For years after that war, blame was assigned as much or more to those

who tried to stop the carnage than to those who carried it out. "Through the Vietnam War, American poets divided the country,"

the Poetry Consultant of the Library of Congress said in a Washington Post interview a full decade after the war. I

called the distinguished poet and shared my opinion that the politicians, not poets, divided the country. In

The Death of Sardanaplus and Other Poems of the Iraq Wars I satirized that exchange:

"HARMLESS POEMS", AN OXYMORON

I still find it easy to recall how we poets cleft

our nation in twain, broke the hearts of mothers,

almost brought down the government by flinging

sonnets through the air, launching sestinas from far

out at sea. Poets torched cities with flamethrower

ghazals and machine gun gathas…

In A Poetry Reading Against the Vietnam War, Robert and I rounded up choisis morceaux of anti-war poems, Nazi propaganda, news

clippings, satires, etc. Here's a typical quote from a U.S. pilot interviewed in The New York Times a month after my son Samuel's

birthday: "I don't like to hit a village. You know you are hitting women and children, too. But you've got to decide your work is

noble and that the work has to be done." Prithee, Sir, tell me why you've got to decide the work is noble.

Soldiers in Iraq are making similar statements today, and there is a great deal of propaganda voluntarily offered by the media

to make them continue to think their war is noble, lost lives worth any price. Curiously, one of the strongest anti-war statements

we chose for our book, "I Sing of Olaf," by e.e. cummings, was censored by his publisher, who would not let us use it.

In the copies that had not yet gone out we had to black out the entire page.

In our little book we included a passage from Freud, who wrote about how "the community no longer raises objections when

men perpetrate deeds of cruelty, fraud, treachery and barbarity so incompatible with their level of civilization that one

would have thought them impossible."

And our good gay gray poet Walt posthumously contributed a shortie:

TO THE STATE

What deepening twilight - scum floating atop of the waters,

Who are they as bats and night-dogs askant in the capitol?

What a filthy Presidentiad…

Then I will sleep awhile yet, for I see that these States sleep…"

Walt Whitman

Did our little book help raise consciousness? Some of its selections such as Goering's speech at his Nuremberg Trials

crop up in protests against the present wars. The propaganda of all wars sound like boilerplates with only minor variations

fed to unwary audiences. All tyrants are, in the words of General Sadao Araki on the eve of the Japanese seizure of

Manchuria in 1931, "exceedingly sorry that our enemies do not yet understand our sincerity. It is our mission to struggle

against all acts incompatible with freedom and self-determination…We have no other intention than to realize, with all its

power, the fundamental ideal - the preservation of peace." Haven't we heard this a few times, including lately.

I understand that the "decider" of the present war is extremely vexed with the Iraqis for not being sufficiently grateful

for what we've done for them.

Can poems help heal wounds of such horrors, such violations of common sense?

Whether yes or no, we must go on writing, for as Neale Donald Walsch writes in Conversations With God:

"You are always in the process of creating. Every moment. Every minute. Every day…you are a big creation machine,

and you are turning out a new manifestation literally as fast as you can…" You are meant to be "a light against

the darkness." As Quakers sing, "Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine!"

But here's a satire on how it often comes out.

AT THE POETRY SOCIETY

She came up to buy a book and get it

inscribed, one of the most welcome duties

of writers, but my pleasure was short lived.

"I just love your wit," she said, "your poems

are so entertaining." She loved the one

about the child of Baghdad killed

by a smart bomb, and the others about

corporate mass murder at Bhopal,

and she loved the Holocaust, or rather,

my poems on the subject, especially

"A Song for Herr Hitler,"although

she wondered if I really admired him.

On and on she babbled, for she found

all my work enchanting. Christ,

I thought, how have I gone wrong?

She had misread me big time. The poems

were my bleeding heart, delivered by hand.

They were confessions of my sins

and crimes, and some were so ironic

that to miss the message was to commit

slander and libel. These poems

she had misread were my guts, spilled

like those of a gored horse in the Seville

corrida, so beloved by Hemingway.

This little lady had reversed the polarities

of life and traded Goya's horrors of war

for Norman Rockwell's Saturday Evening

Post paintings of freckled boys in chairs

of dentists or barbers Yet, after reflection,

I felt a surge of gratitude for her mentoring,

for should I not give up and rest on my laurels?

(unpublished)

Despite such encounters, my feeling toward readers is still what it was as expressed by one of my shorties:

THE FAMILY

Rounding up the family one chick

and kitten at a time, I see that even

the fly on the barn wall becomes

someone for whom I was searching.

Gathering Firewood

PLEASE TELL US WHAT IT WAS LIKE TO WRITE YOUR MEMOIR, "THE ENDLESS SEARCH."

Writing autobiography is a near automatic experience once you take off from an incident or reflection on your past.

The Endless Search was merely the tip of an iceberg, about a third of the story, for a sequel languishes in manuscript.

I believe that writing is therapeutic, though as James Dickey said, "The trick is to climb in with the alligators but

make sure you can get out." There are a lot of alligators in any pool you leap into.

WHAT IS YOUR LIFE LIKE NOW?

When I sailed to Europe on the S.S. Rhyndam in 1966 I wrote a poem, later published in Dragging the Main, that anticipated

my present life. The poem was inspired by a white jacketed steward I saw leaning over the rail at the stern. He leaned

forward, gazing at the sea and the ship's moonlit wake. Watching him I thought of Melville's Redburn, the young sailor,

and the older Ishmael, and Melville himself. Somehow the vision was of a long and a serene life, a vision has survived as

counterpart to my despairs.

THE STEWARD

The sixtieth gull.

It begins to rain.

He turns too, in his

White coat, throws

His cigarette into

The sea.

It is time to return

To those who do not

Love him, to babble

Their children

To sleep, to be

Part of the hum

Of the ship's engines.

The nights sail

Away, on the oil

Of manners and charm.

But once

They stuffed with wicks

Those white gulls

Of the English Channel

And burned them for

Lamps, when Stuka

Provided the birds

And shore-watchers went

Dizzy. It takes

(This sea where we

Rock) the fieriest

Gulls, and it makes

The Stukas and

Messerschmitts fall

In a mist so thick

Few remember. And it

Gives for a bonus

The calm of white-

Jacketed years.

Dragging The Main

But, to return to your question: With my poet wife Judy, who saves my life two thousand and three times a day, and our

love for three grown daughters, lost son, and three grandchildren, not to leave out our loyal mutt, Levi, I have found

some serenity in my life, and am beginning to assign the past to deep time. The Quakers too have been important. Of

them I say "I don't have any faith, but I like to sit among people who do."

When I retired from my professorship at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, I had already been thinking a lot about

simplifying and downshifting, as reflected in some poems.

TUNING OUT

Space becomes sacred.

Don't wait for the grave.

A small shack will do.

Or perhaps none.

One cart for possessions,

none spilling over.

Just walking - an end

to that car crap, big house

and big chair crap,

stocked pantry,

bars on window,

gold coins, stocks

stashed, plastic cards

the poor don't have,

basement bomb shelter

and one in your head,

all secrets kept.

More cactus, more sun,

less bought and more thought.

New Letters, 1996

"My life is not perfect, nor is it close to being perfect," Neale Donald Walsch wrote in Conversations With God.

In my own way I have followed my bliss, but rarely did I realize it was bliss and that despite myself I have followed a

spiritual path all along, even when I was struggling for mere survival as top priority.

Literature has been a big part of my life, spiritual and practical. I could list a thousand writers who have done their

share in propping me up in my bed of woe and pointing out the light. And God bless Donald Bond, one of my professors at

the University of Chicago. In his class on Eighteenth Century Literature he asked us to write about what we would like

to be and do. Without hesitation (or pride) I wrote that I would like to be a writer (I already was), an editor, and

scholar. Strangely, I have managed to cover all three bases. Soon I became editor of Chicago Review, then went on to

help edit Epoch, found New Letters and New Letters On the Air radio program, and edit several anthologies and the books

of several writers.

One of the three ambitions in this triad, my "creative" writing, we have already discussed. As for scholarship, I have

researched many articles, including several in the St. James Contemporary Poets encyclopedia and one in the

Autobiographical Series of the standard reference series, Dictionary of Literary Biography. My research for both

published and unpublished books, such as my manuscript novel based on the lives of the Lindberghs and my collection

of poems about Hemingway - and many individual poems and stories for that matter - has been extensive, requiring work

in archives such as those at the Library of Congress and the National Archives.

My fat book of collected essays, still in manuscript, is about as scholarly as a poet can manage without becoming a bore.

When I retired from the University of Missouri-Kansas City (let me boast, as one does in interviews), I was listed among

the one hundred most distinguished individuals "whose efforts created a significant impact for this university," and more

specifically among the top seventeen "Scholar-Teachers" of the first seventy years of the university. What a surprise!

(See Perspectives, the News Magazine of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Winter/Spring, 2000.)

Day by day I am becoming aware of the bliss we are born to, and my luck of having survived to write each word you read.

And I am glad it was not bloody battlefields that I've survived. I am grateful that most of my crimes were misdemeanors.

YOU WRITE IN ALL GENRES. WHAT ARE YOU WORKING ON AT THE MOMENT?

I am deep into a story that feels like it will turn out to be a novel. It is not the first novel I have written, though none

are published. You say "at the moment," so I'll also tell you that at high noon on my 75th birthday, I worked on a letter to

our Arizona governor trying to stop the state's first execution in six years. It was also the day the New York Times Magazine

published my letter to the editor criticizing superficial journalism they had published about clinical depression. I am tempted

to include as a legitimate genre the thousands of Letters to Editors and Opinion columns, both published and unpublished, I have

written over the years, hoping to weigh in on crucial issues. Needless to say, there are often vested interests that block these

efforts, but some of these mini-essays get through.

I also write new poems nearly every day. When I run into another poet who is not ashamed of turning out more work than is

fashionable, I feel relieved to have found honorable company. One morning before 7 a.m. at the Banff artist colony in

Canada, I encountered Bill Stafford. "Have you written a poem yet today?" I jibed. "Three," he said with a grin.

Now there's a dangerous example!

HAS THE WRITING BROUGHT YOU A MEASURE OF PEACE?

Yes, and perhaps something of the serenity of "The Steward." Perhaps that's what I was aiming for all along, but didn't know it.

FOR THE INTERVIEW

For Gloria Mindock & Susan Tepper

Leave out the negative.

Stress the positive.

You dare not brag

though Mark Twain

said "Blow your own

horn lest it be not blown."

And do not rant or admit

you weep each day

for all that's wrong

and because you can-

not stop the war

or what fools do

in Washington. Above

it all, remember

that readers glean

the gossip, so serve

a bite but not too big.

And if there's time

consult your list

of words never ever

to use in poems,

the list that begins

with never and ever.

XXX

|