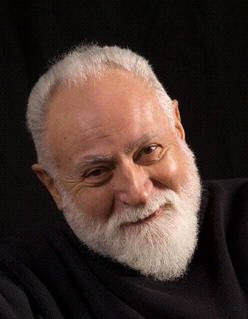

INTERVIEW WITH DJELLOUL MARBROOK

Write a bio about yourself.

I was a few months old when my mother brought me from Algiers to her mother and sister in Brooklyn. I think she had stopped

over in France and England, but I never learned why. My grandmother, Hilda, said I looked like a plucked chicken. Her doctor

told her I probably wouldn't survive. But Grandma was determined I wasn't going to die on her watch, so she strained soups and

spoon-fed me. She took me to Coney Island every day to take in the sea air, and I slowly got well. When I was five my mother,

seeing that I regarded Grandma and my Aunt Dorothy as my mothers, sent me to a

Christian Scientist boarding school on Long Island.

There was trouble from the start. I arrived in America under a cloud of myth. My mother claimed my father had died of a hunting

accident while she was pregnant. It wasn't until 1992 that I found out he had lived until 1978. It turns out that although he

had had an affair with my mother, he chose to remain with a Scottish woman with whom he had been living. After the Scot's death

he had three children with a woman who is still alive in Algeria. I have corresponded with this family.

I got a superb English education at the boarding school until I was 15, because English people had founded the school and

many of the students were wartime evacuees from England. But I suffered sexual molestation of various kinds and brutality

from bullies. I also learned how to take care of myself and to confront bullies.

I then lived for three years with my mother and stepfather in Manhattan, attended a marvelous prep school and continued to

excel academically, but I had never seen drinking or smoking before, and the household was violent and upsetting.

The presence of alcohol proved to be dangerous. I quickly became a secret alcoholic. In college, at Columbia, I did well for

two years but began missing classes and neglecting studies. I didn't know it, but I was looking into the abyss, a first-class

psychotic break. The day before my 18th birthday in August my mother kicked me out. We had never gotten along very well. My

stepfather was now elderly and ill. In a few more months, living alone, I broke down. One day everything just got too big,

too loud, too close, and I put my books down on a bench, got on a subway train and never returned to college. It never occurred

to me that I had what then would have been called a nervous breakdown.

I served in the Navy on active duty for five years and then reserve duty and started a newspaper career in

Rhode Island at The Providence Journal.

I wrote poems from age 14 into my late 30s, but at some point I recognized that I didn't want to be caught

dead saying what I meant or meaning what I said. So I stopped writing poems, but I kept on reading poetry and

studying poetics. In 1971 a doctor told me I was about to die of alcoholism. Then followed a long struggle to

stay sober and deal with the underlying depression that I had used alcohol to medicate. Once I had been sober for

a few years, it dawned on me that I was an adolescent. I've been spending my life since then trying to grow up.

I started writing fiction in 1989, thinking it might be my real calling. But something about the terrorist attacks of

September 11th, 2001, awakened me to my own poetic impulse, and I started walking around Manhattan writing poems.

People would look at me and smile, and I'd smile back, and after a while I said to myself, This is my city, my hometown,

and I love it, no matter what happened to me here, no matter how savage the memories I have to relive, I love this city

and I'm going to say so. I'm going to take it back from the family that found me so inconvenient. I didn't know it then,

but many of the poems would be about being inconvenient to others, about feeling less than welcome in situations where

people were patting themselves on the back for welcoming you, about always being invited to treat your own intuition with

contempt, and being punished if you didn't accept the invitation.

Describe the room you write in.

My usual practice is to walk around Manhattan or upstate towns and country roads, scribbling the makings of a poem

into notebooks. So my room is usually a country road or city streets, sometimes a café. I'm kind of particular about

the notebooks. I favor translucent plastic covers and telescoping ballpoints. But I'll write on napkins and newspapers

if I have to. I sleep with a large notebook and pen, because I often wake up with a poem in mind. When I'm in our

apartment in Manhattan I tend to write in our dining area under a large painting by Andrew Franck, a Woodstock

homeopathic doctor, artist, musician and alchemist. Upstate in Germantown I write all over the house, but my

favorite spot is a light-filled front room where one of my mother's paintings hangs. It's called Plateau of the

Green Moon. (I can give you a jpg image of it if you wish.)

At some point I transcribe my notebooks to a laptop-I rarely carry a laptop around-and then most poems go through who

knows how many changes. I never really stop working on a poem. Some come easily. Others daunt me. If something about a

poem is eluding me, I usually call it a draft and keep it on my computer desktop. But I keep the notebooks handy, too,

even when they're filled, because sometimes I see something I want to change or add when I glance at my handwriting.

The handwriting often gives me a clue, an insight that formal typography doesn't. I can relive a recognition by

examining my handwriting. Sometimes my handwriting is quite studied and formal; other times it's hurried and ragged.

That tells me something about my original impetus to write a poem, and I find that important, because I fear perfecting

a poem to the point where it is so studied that it has left behind the original idea.

In 2007, your manuscript won the Tom and Stan Wick Prize for poetry from Kent State University. Your first poetry book,

Far From Algiers, has just been released. Talk about your book.

A few years ago I woke up in the middle of the night-which I often do-feeling overwhelmed by what I had written. I

felt that I needed to reconnect to it. I started to make stacks on the floor of our front room upstate in Germantown.

I ended up with 15 stacks for as many general categories. But the stacks were quite uneven. I noticed that the 11th

stack was by far the tallest, and it seemed to me that these poems were about belonging and unbelonging, about them and

us. I saw that I belonged to them, whereas my mother's family, it seemed to me, belonged to us. I began to see this as

the central crisis in my life. But of course it wasn't that simple. Nothing ever is, our fundamentalist friends

notwithstanding. I saw, for example, that my presence had opened up wounds in my mother's family. If I had looked

like them, the wounds would have been superficial, but I didn't look like them, so I had to be the outsider. Not

that there wasn't immense love and devotion from my grandmother Hilda and my Aunt Dorothy, my mother's younger sister,

but it couldn't protect me from that sense of foreignness, of being the family issue, the problem.

I don't know how the title came to me. There is a title poem, so I suppose I just fell upon it, thinking it would convey

that sense of struggling to belong in a situation where I was perceived as a problem. My mother's family felt she had handled

matters badly, and I was one of the matters. I think in time she came to resent the solution, which had been to park me with

Hilda and Dorothy. Predictably, I came to feel I had two mothers, Grandma Hilda and my young Aunt Dorothy. So, when I was five,

my mother removed me to a boarding school, and I don't think Hilda and Dorothy ever forgave her for that.

At some point I became dimly aware of the nature of my rebirth as a poet. My hometown, New York, had been attacked. I

felt injured and angry, as all New Yorkers did. But I noticed that at the same time we were all coming together there was

also this bitter response, the flag-waving, the underlying message that if you didn't hate somebody, if you didn't want to

bomb anybody the president might select for bombing, then you weren't American and you didn't belong. So while we were

grieving and coming together, some of us were also venting nativist, them-and- us sentiments, which of course are at play

in the elections. This called up my own lifelong struggle with the them-and-us syndrome, and in this case the Arabs were

them. My father of course had been an Arab. I had no doubt about my Americanism, my patriotism. But I could readily see

that what some Americans meant, without saying it out loud, was that if you didn't look North European you were essentially

suspect. And if you didn't look acceptable, then at very least you had to support any response the extreme right might cook

up to deal with the situation so that you could prove yourself to the rest of the country. But who was the rest of the

country? At best, some 25 percent of Americans are white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Certainly not anywhere near a majority.

The U.S. Army, I could see, looks like the whole country, like our demographics, but the governments we're electing do not.

In the news footage from Washington you can see our federal government doesn't look like our army, it doesn't look like the

sons and daughters we are sending to die for us. So I began to see that I had opened a wound, not only in my own soul but

also in the country's. I took a deep breath and put a manuscript together, and it was my great good luck (or was it

synchronicity?) that Toi Derricotte read the manuscript, because she had suffered that very wound and understood it well.

(To order: http://upress.kent.edu/books/Marbrook_D.htm )

Talk about your book, Saraceno. How long did it take to write? You had personal experience with the Mafia to write this book.

How did your life growing up influence this book of fiction?

Saraceno was my very first work of fiction. I started it in February 1989. I was in Woodstock, nursing Bill, my mother's

second husband. My mother, then 85, was unprepared to cope with his illness. He lived in a beautiful little 1880s

Italianate cottage next to a famous old hotel built by his grandfather in 1929. It had last operated in 1964. In

the evenings when he fell asleep I would sit in the lobby of this ghostly unheated building, pecking away on an antique

Oliver, one of the many things Bill had collected over the years. Every once in a while I'd get up and throw a piece of

broken furniture into a huge fireplace.

What emerged was an encounter with a Hell's Kitchen thug named Billy in the early 1950s. At that time I was struggling to

stay in college. My mother had kicked me out, and I had already become alcoholic. I was working in a cigar store on

Eighth Avenue, selling newspapers out front. Billy had just spent seven years in Dannemora. He was extraordinarily

handsome, self-possessed and breathtakingly violent. He had been sentenced to Dannemora for savagely beating a cop.

I liked him, and sitting so many years later in that windy hotel with the fire crackling, I recognized that I wanted

to write about him, to imagine what might have become of him. I had played a role in connecting him to La Famiglia.

The Mafia was a subject I could write about with some authority, at least its cultural aspects, because my stepfather,

Dominick, was a Sicilian and had been a chum of Charlie (Lucky) Luciano. I felt I could say something that hadn't quite

been said before about the Mafia. But mostly I wanted to write a story about friendship and honor in an unlikely place.

Saraceno was printed but never distributed, although new and used copies are trading actively on the web. The small

Canadian publisher failed before distributing the book. But because it was a print-on-demand book published by BookSurge,

Amazon's POD subsidiary, Amazon kept reordering it until I realized it hadn't been distributed or promoted and withdrew

the copyright. So some copies are still out there in the world, and it still gets a surprising amount of attention on the

web. And of course POD books are ignored by the mainstream media, for the most part. The book got some good reviews, and I

had hoped it would open the door to publishing some of my other fiction.

Several months ago a story taken from an unpublished novel won Literal Latté's first prize in fiction.

It will be included in a Literal Latté anthology.

You worked as a reporter for The Providence Journal. How long did you do this?

Did any of the stories you covered fuel your writing?

I had been contributing to The Journal when I was stationed at Quonset Point in the Navy. When I was discharged The Journal

amazingly gave me a chance during one spring and summer to compete with journalism school graduates for a job. I had no degree

at all, although I had studied for three years at Columbia and was something of an autodidact (I still am). I

stayed with The Journal from 1958 to 1964. And yes, I'm sure some of the stories I covered influenced my writing,

but not as much as my experience working as a teenager in Manhattan. I then became an editor at a number of newspapers

and finally an executive editor for small and mid-sized dailies. By the time I managed to stop drinking and start

growing up, journalism had changed and so had I. I was fiercely idealistic, unrealistically so, and as a sober and

reasonably self-aware person I kept butting up against the commercial censorship and distortion of news that is pervasive

in the mainstream media. I wasn't able or willing to make the compromises necessary to go along and therefore get along.

It was a form of immaturity, but also an awareness I hadn't had before. I didn't feel in any way superior to all those

wonderful colleagues who could get along in the business. In fact, I felt inferior, disabled in the way that persons with

learning disabilities are handicapped. And by this time I was past 50. I had no illusions about being successful as a

fiction writer. But I did think I had something to say, which hadn't been the case before. I knew I didn't want to write

thrillers or police procedurals, but I knew my head was teeming with characters who wanted to be heard.

I had no idea what I was up against trying to get published, and to make matters worse, I'm not a networker. I have trouble

enough answering the phone, much less picking it up and trying to interest a stranger in anything I'm doing. I feel about

that sort of thing the way I feel about walking into a gallery in a museum-I'm intruding on the painting and the painter.

I have no business in his or her head. If I look at Primavera I start thinking the hounds of Diana are going to hunt me

down and tear me to pieces. Everybody else's privacy is so sacred to me I can't imagine how I could have presumed to be a

reporter. Maybe that's why I became an editor. I think the way we intrude on each other in the popular press is obscene and

savage. And yet I'm perfectly willing to call the intrusions of Virginia Woolf and D.H. Lawrence art. Well, who said we're

obliged to make sense?

You were editor for many newspapers including The Elmira (NY) Star Gazette, The Baltimore Sun, The Winston-Salem Journal

and Sentinel, The Washington Star, and Media Newspapers in Northeast Ohio and Patterson and Passaic, NJ. What was this

experience like? What were the challenges you faced?

Working for The Journal was halcyon. Working in Elmira was formative and deeply rewarding. I learned how to get a newspaper

out onto the street, how to design one, how to follow production from start to finish. The Baltimore Sun instilled the value

of excellence, taking pains, precision, high literacy. But The Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel gave me the most hospitable

and gracious work environment, the loveliest people, and the most memorable period in my newspaper career. The people in Ohio

were unfailingly friendly and welcoming, but the work there and in New Jersey was exhausting, demanding, and filled with the

challenges of trying to do more with less. The entire industry had changed by the mid-1980s. Newspapers were cutting back

ruthlessly, trying to find new ways to engage readers, and hoping that by stringencies rather than investment they could

turn the industry around. I think we put out very good newspapers, but each day was a tour de force rather than a steady

march of good journalism, and I simply wasn't up to the long haul, whatever that might have turned out to be.

How long were you the English editor for Arabesques Literary and Cultural Review? Recently, their website disappeared.

Do you know what happened? I have had work published in this magazine. I loved their diversity in publishing.

Talk about your experience. Let's hope this journal will be back soon.

It recently reappeared on the web, with a bit of help from my wife Marilyn and me. I am still an advisory editor for the

English version, but I find I don't have the time to actively edit each contribution. Arabesques is a brave venture by a

young Algerian poet in the western city of Chlef. Amari Hamadene has been struggling to find the resources to publish

literature and cultural inquiry in French, Arabic and English. It's an immense task of bridge building between cultures

that are often in conflict. Amari's design sense is superb, and if there were any justice in the world his own government

and the French- and English- speaking worlds would support his endeavor, because the news we get is about oil, terrorism,

sectarian conflict, instability, death-whereas there is good news and good will throughout the world, and Amari's project

is a bright instance of that. What he's trying to do is more important than the latest oil price or terrorist attack, but

the media don't see things that way. He published the title poem of my book, Far From Algiers.

You are a regular contributor to the Istanbul Literary Review. I always look forward to reading and publishing your work.

Talk about the importance of international magazines.

The vogue is to think we are on information overload, but the creative thinking, the recognitions that challenge our

minds and hearten us are conspicuously absent in the mainstream media. On television the Discovery and History channels

are infinitely more edifying than cable news or the networks. In the print medium The New Yorker is far more likely to

enlighten us than newspapers. Editors have been supplanted by marketers who regard culture as a horse race and define

success as winning. Under the circumstances, the small presses and journals like Istanbul Literary Review are essential

to the exchange of ideas and the nurture of creativity. And among these the international journals like ILR and Arabesques

fulfill a special role, because they transcend national boundaries and free artists and thinkers to communicate on a

grander scale. They transcend the fundamentalism that plagues the world in almost every culture. Fundamentalism in essence

is the impulse to control other people's minds, to limit perspective and inquiry, to impose inquisitions and dampen

ecstatic wonder. The international journals stand over and against all this. The tension in the world is not essentially

a response to Western capitalism, as seems to be the popular perception, but rather a conflict between the spirit of

inquiry and the fear-driven compulsion to shut inquiry down and impose dogma. The tension is political only in the sense

that governments respond to one impulse or another. So anyone who is about building bridges between cultures and the free

exchange of ideas stands against putting the human mind in lockdown.

Your mother, Juanita Marbrook Guccione, and her sister, Irene Rice Pereira were famous painters. What was it like growing up

in such an artistic family?

I lived with my mother for only about three and a half years-the first few months of my life in Algiers and England, when I

was deathly ill, and then between the ages of 15 and 18 in Manhattan. Our relationship was troubled but profoundly involved.

After her death I could see quite clearly that I had always been a reminder of something that had gone terribly wrong in her

life, and I was overwhelmed with sorrow about that. I had always felt like an intrusion. Her paintings were her children, and

now they're mine, and it's up to me to see that the world sees them. It was exciting to be around my mother and my Aunt Irene.

My relationship with Irene was serene, untroubled, and deep, because we shared an interest in metaphysics, history, the life of

the mind. Irene was always a quiet refuge for me, and I admired her inordinately as a painter and a person. My mother was a

great beauty, the kind men gape at in the street. This was both useful and problematic for her. Few people ever got past her

looks to know her. Irene was also beautiful, but not in such a conventional way. Nobody made a big play for Irene unless they

thought they could deal with that fierce intellect. I once mentioned that to her. She smiled, turned into the kitchen to make

us tea and said over her shoulder, 'You're perceptive.' My mother was inclined to think men make fools of themselves over women.

She often looked at me as if she didn't have the faintest notion where I came from. I loved this, while at the same time it

chilled me. I thought she really didn't have the faintest notion, and neither did I, since she had mythologized her

relationship with my father and assigned to him a premature death, which was rather like sticking pins in a doll.

Certainly my mother and Irene instilled in me a lifelong love of art. I thought they were gods, no matter what else I

might see in their lives. I thought they weren't subject to the same rules as mortals, and my mother certainly agreed.

Irene, on the other hand, reserved her contempt not for people who disagreed with her but for soap opera. She loathed

melodrama and exhibitionism.

Since you were born in Algiers, when did you move to America? Talk about your immigration experience.

Do you ever go back to Algiers?

It wasn't an immigration experience in the usual sense. I was an infant when I arrived in Brooklyn at Grandma's home. I don't

know where my mother took me when she left Algiers. I was a few weeks or months old. I don't know the exact time line. So I

have no memory at all of Algeria, which is probably a blessing, since I was born to a troubled trio, my young father, my mother,

age 30, and my father's rich companion, who was in her forties. Maybe surviving didn't seem like an

option to me.

I remember my first five years in Brooklyn with a good bit of clarity. Grandma hired a wonderful nanny, Peggy, whom I

worshipped, and between Peggy and her family and Grandma and Dorothy I was very happy until the day my mother pulled me

out and sent me to boarding school. Dorothy was athletic and used to roller skate and ice skate with me on her shoulders,

and I have fond memories of sitting on her shoulders and Peggy's too, braiding their hair. From Grandma, Dorothy and Peggy

I acquired the notion that nothing untoward in my life would ever come from women. But boarding school was to shockingly

disabuse me of that notion.

Is your wife Marilyn a writer?

She should be. She would be a wonderful writer. But she has chosen to be an editor. She edited and published reports

for the Justice Department in Washington for many years, and dozens of their documents and books bear her name. Now she

is my editor, and without her I would never get a thing published. She has an unerring feel for language and is a

voracious reader. Once she retired she took to submitting my work, and that has been a godsend, because I despair at

the drop of a hat.

What are you working on now?

I'm busy scribbling in notepads and editing the fiction I've already written. In a sense I never finish anything.

I could go back into Far From Algiers and make changes, but would they be improvements? I've learned from painters

that artists rarely know which work is best. I have written three novellas, The Pain of Wearing Our Faces, Artemisia's Wolf

and of course Saraceno. The Pain and Artemisia are about women artists. Artemisia is an homage to Artemisia Gentileschi and

my Aunt Irene. I have been working since 1989 on a long novel whose title keeps changing as I keep editing and revising. I'm

not sure of its final shape, although it is essentially done. Perhaps it should be a duo or a trilogy. I'm undecided. I live

in this novel day and night. I dream of it. For a long time I called it Salvor's Deep. Then Diver's Angels. I hope to finish

revising it this winter. The Literal Latté winner is an excerpt from it.

Any comments?

If I've made a connection with any readers, they might wish to stay in touch with me by visiting my blog at

www.djelloulmarbrook.com. I post short essays and art with some frequency. I started it to promote Saraceno.

Now I hope it is promoting Far From Algiers. Over time it seems to have become useful for sorting out my thoughts.

|